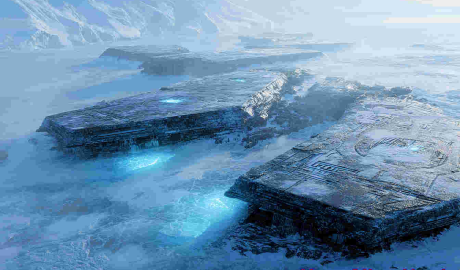

Antarctica: A Land of Ice, Silence, and Secrets

From Cosmic Particles to Alien Ruins, What Hides Beneath the Frozen Veil? Antarctica is Earth’s final frontier — not in terms of distance, but in mystery. Despite decades of exploration and research, this vast, ice-locked continent continues to baffle scientists and inspire fringe theorists, adventurers, and science fiction writers alike.Continue Reading